Stories of mermaids exist in many cultures around the world, with varying descriptions and characteristics.

The English word “mermaid” is a compound of “mere” (Old English for sea) and “maid” (a girl or young woman).

Essentially, it means “sea-maid.”

While the specific term “mermaid” might be relatively recent, the concept of mythical sea creatures with human-like features has existed for millennia in various cultures worldwide.

Mesopotamia: The concept of a being with both human and fish characteristics appears in ancient Mesopotamian mythology, particularly with the god Ea, often depicted with a fish tail.

Assyria: Around 1000 BC, the Assyrian goddess Atargatis, associated with fertility and the sea, was said to have transformed into a mermaid after an accident.

Greek Mythology:

Sirens: While initially depicted as bird-women, sirens in Greek mythology gradually evolved to resemble mermaids, luring sailors to their deaths with enchanting songs.

Other Cultures:

Africa: Mami Wata is a water spirit in many West African cultures, often depicted with a snake or fish tail, representing both beauty and danger.

Ireland: Merrows are Irish sea creatures with green hair, often depicted as benevolent but sometimes mischievous.

Japan: Ningyo are Japanese mermaid-like creatures, often associated with good luck.

Folklore of Britain and Ireland

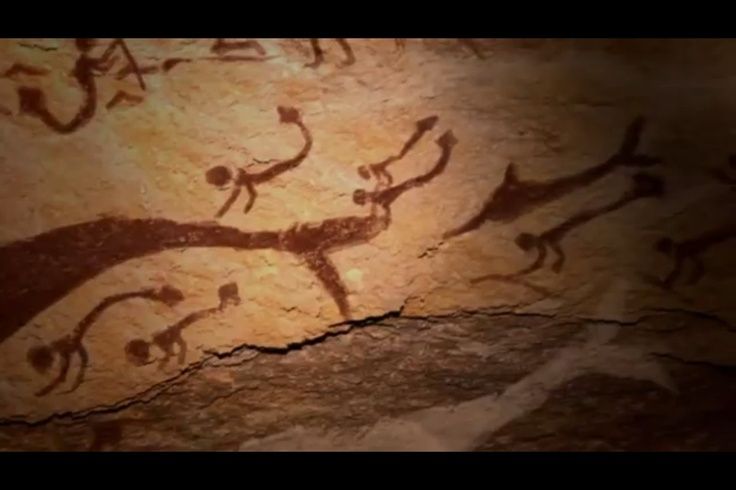

The Norman chapel in Durham Castle, built around 1078, has what is probably the earliest surviving artistic depiction of a mermaid in England. It can be seen on a south-facing capital above one of the original Norman stone pillars.

Mermaids appear in British folklore as unlucky omens, both foretelling disaster and provoking it. Several variants of the ballad Sir Patrick Spens depict a mermaid speaking to the doomed ships. In some versions, she tells them they will never see land again; in others, she claims they are near shore, which they are wise enough to know means the same thing. Mermaids can also be a sign of approaching rough weather, and some have been described as monstrous in size, up to 2,000 feet (610 m).

In another short ballad, “Clerk Colvill” (Child ballad No. 42), the mermaid seduces the title character and foretells his doom. It has been surmised that in the original complete version, the man was being penalized for spurning her, though the Scandinavian counterparts that tells the complete story feature an elf-woman or elf queen rather than mermaid.

Mermaids have been described as able to swim up rivers to freshwater lakes. In one story, the Laird of Lorntie went to aid a woman he thought was drowning in a lake near his house; his servant pulled him back, warning that it was a mermaid, and the mermaid screamed at them that she would have killed him if it were not for his servant. But mermaids could occasionally be more beneficent, e.g., teaching humans cures for certain diseases. Mermen have been described as wilder and uglier than mermaids, with little interest in humans.

According to legend a mermaid came to the Cornish village of Zennor, where she used to listen to the singing of a chorister, Matthew Trewhella. The two fell in love, and Matthew went with the mermaid to her home at Pendour Cove. On summer nights, the lovers can be heard singing together. The legend, recorded by folklorist William Bottrell, stems from a fifteenth-century mermaid carving on a wooden bench at the Church of Saint Senara in Zennor.

Some tales raised the question of whether mermaids had immortal souls, answering in the negative.

In Scottish mythology, a ceasg is a freshwater mermaid, though little beside the term has been preserved in folklore.

Mermaids from the Isle of Man, known as ben-varrey, are considered more favorable toward humans than those of other regions, with various accounts of assistance, gifts and rewards. One story tells of a fisherman who carried a stranded mermaid back into the sea and was rewarded with the location of treasure. Another recounts the tale of a baby mermaid who stole a doll from a human little girl, but was rebuked by her mother and sent back to the girl with a gift of a pearl necklace to atone for the theft. A third story tells of a fishing family that made regular gifts of apples to a mermaid and was rewarded with prosperity.

In Irish lore, Lí Ban was a human being transformed into a mermaid. After three centuries, when Christianity came to Ireland, she was baptized. The Irish mermaid is called merrow in tales such as “Lady of Gollerus” published in the nineteenth century.

Over time, these various myths and legends blended and evolved, contributing to the modern image of the mermaid as a beautiful, often alluring, creature of the sea.

Mermaids are sometimes associated with perilous events such as floods, storms, shipwrecks, and drownings. In other folk traditions (or sometimes within the same traditions), they can be benevolent or beneficent, bestowing boons or falling in love with humans.

The male equivalent of the mermaid is the merman, also a familiar figure in folklore and heraldry. Although traditions about and reported sightings of mermen are less common than those of mermaids, they are in folklore generally assumed to co-exist with their female counterparts. The male and the female collectively are sometimes referred to as merfolk or merpeople.

Native tribes

The Halfway People of the Mi’kmaq

In Mi’kmaq folklore, a captivating tribe of beings known as the Halfway People hold a special place. These enchanting creatures, often depicted as having the upper body of a human and the lower body of a fish, are said to inhabit the depths of the sea, their presence shrouded in mystery and wonder.

The Halfway People are not merely mythical figures; they are deeply intertwined with the Mi’kmaq worldview, representing the delicate balance between the terrestrial and aquatic realms. Their existence serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of all living beings and the profound respect that should be accorded to the natural world.

There is also a Sekani legend about a man who married a mermaid. He captured her by tying her to a tree by her long hair. During her first winter on land she begged him to let her return to the water. During her second winter her husband wasn’t able to kill much game so he let her return to the water. She brought him and their son food and returned to him.

“After this the mermaid lived very happily with her husband for many years and bore him several children,” the legend says. “Very reluctantly he consented and dug a hole through the ice for her. She dived into the water but returned immediately because her children were unable to follow her. One after another she rubbed their mouths with water and told them to dive in after her. Then they all went down into the water and never returned.”

Another legend called “The Lost Boy” comes from the Lenape. It tells the story of three boys crossing a normally calm, shallow stream. One of the boys was lost when a wave came rushing at them. The boys’ parents went to a mystic man to find their lost son. The man told them their son was alive and had been taken by a woman. The mystic man told them they could see their son at sunrise if they camped on the bank of the great river.

An Ottawa tale tells the love story of Menanna and Piskaret. Menanna showed up at the door of an Ottawa warrior, covered in scales with twin fishtails where her legs should be. She told him she had once been mortal but longed to roam the heavens. The Great Spirit granted her wish, but she grew tired of wandering and was allowed to return to earth, though in a form “neither mortal nor immortal, neither man nor beast—the mermaid shape in which the warrior beheld her. In this guise she became the adopted daughter of the Spirits of the Flood.”

The warrior took her in and the scales began to fall away, but she wouldn’t regain her original human form until she found love. When she did find love, it was with Piskaret, the son of an enemy tribe—the Adirondacks, who refused their love.Menanna was so sad she left the Ottawas and rejoined the Spirits of the Flood, who vowed vengeance on the Adirondacks.“The Spirits of the Flood attacked the canoes of the Adirondacks, leaving few of the tribe alive. Piskaret was caught and shielded in the arms of Menanna, who drew him from his canoe and sank with him beneath the waters

5 True Ghost Stories of Knoxville Tennessee

5 True Ghost Stories of Knoxville Tennessee  The Minds Last Stand: The Third Man Factor

The Minds Last Stand: The Third Man Factor  Shadow Figures: They’ve Been Watching You All along

Shadow Figures: They’ve Been Watching You All along  The Bigfoot Mystery of Mt Saint Helens

The Bigfoot Mystery of Mt Saint Helens  Bigfoot’s Hidden Rage: Why some Encounters turn Deadly

Bigfoot’s Hidden Rage: Why some Encounters turn Deadly  Cheating Death at the Quantum Level

Cheating Death at the Quantum Level  Into the Unknown: Exploring the Michigan Triangle

Into the Unknown: Exploring the Michigan Triangle  The Shag Harbour UFO Incident

The Shag Harbour UFO Incident